Archive

United Kingdom should vote to Remain

I am deeply concerned for the future in Europe and of the European Union. Many across the continent are looking inward, closing their country to outsiders. Rather than considering the benefits of a diverse society, one that respects the worth of those who seek to make a better life for themselves and their family elsewhere, one that increases the richness of a culture by adding to the variety of experiences within it, populists and nationalists are perpetuating myths about foreigners. We saw this in the strong regional result for Marie Le Pen last year, governments in successive Nordic countries including or dependent on such extreme nationalist parties. We see it in the leading government parties of Hungary, Poland and Slovakia. Last month, we were frighteningly close to witnessing the election of an FPÖ candidate for president.

And we are seeing this now I’m the United Kingdom. This turn was unfortunately aided by the established parties, whether David Cameron’s awful pledge to reduce immigration to the tens of thousands, or Ed Miliband carving Controls on Immigration in stone and on party mugs before last year’s election. Inward immigration is a sign of economic strength. Workers move to where the jobs are, and in turn increase economic activity where they arrive and settle. But this has been ever more blatant from UKIP, the leading force behind this referendum. The worst of this was in the demonisation in the poster unveiled by Nigel Farage last week of those now in Europe who fled to twin terrors in Syria of Assad and Daesh. Aside from the fact that commitments under the Geneva Convention is independent of any obligation deriving from EU membership, I worry for politics and society where a message of abandoning those in distress would be victorious, instead of recognising the need to find solutions to the global emergency of record levels of displacement.

The European Union has been good economically, for individual countries like the United Kingdom or Ireland, and for the continent as a whole. It does this through facilitating trade within the union, and also by acting as a negotiating trading bloc with other countries or global regions. While this includes many regulations, in most cases, these are such that would exist at a national level in their diverse form, and their standardisation is such as to ease the flow of goods. I don’t support all the Union does; in particular, I do not support farm subsidies. But were I in the United States, the existence of federal farm subsidies would seem a very poor argument for secession. On the whole, and in most respects, the European Communities and the European Union have been the greatest project in transnational free trade.

The European Union was a worthy recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2012. From their inception in 1950s, the Communities brought together countries which had fought three major wars in the previous 80 years. With Ireland and the United Kingdom coming in together in 1973, they provided support for the peace process. In the 1980s, they brought in former military and fascist dictatorships, and in the 2000s, the Union welcomed those which had been behind the Iron Curtain. It promoted democratic and economic development before and after entry. The institutions have proven inadequate to guard against regressive steps by governments in Poland and Hungary in recent years, but they would be so much weaker should the Union begin to disintegrate. We need to maintain a strong Union with countries committed to liberal political and economic principles.

Allies of the United Kingdom worldwide have been clear that to maintain their place in the world, they should vote to Remain. In support of Leave, however, are Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump. It would fit their worldview of isolated countries competing against each other rather than cooperating, seeing the European Union as a threat rather than a partner.

Economic analysts are at a near consensus that leaving the Union would be bad for Britain’s economy and indeed that inward migration from the EU and elsewhere has been beneficial. It worries me that a campaign with so little explanation of what would happen next is so close to winning, ahead in some polls, putting the position of their economy and society at risk for an unknown, fed by resentment against foreigners who have managed to gain employment. When Kate Hoey was pressed, she could not name any reputable independent study that showed the United Kingdom would be better off if it left.

Leaving the European Union would weaken the control the United Kingdom has over many of its external trade decisions, bound to arrangements of the remaining 27.

It will have consequences for our island. We would probably be able to maintain the Common Travel Area, but customs restrictions could be introduced, depending on what deal the United Kingdom would negotiate (again, we don’t know what it might be). It would inhibit and hinder the welcome and increasing cooperation across Ireland, North and south. I find it deeply frustrating, if perhaps not surprising, to see Arlene Foster and the Democratic Unionist Party put this stability at risk, perhaps for the reassurance that it would weaken ties south of the border.

Most of all, what concerns me is what a Leave vote would say about the politics and political campaigns that work. In some respects, it is more concerning than the election results across Europe I referred to above, as it is almost certainly irreversible.

So for these reasons, I’ll await nervously for the result on Thursday night and Friday morning, hoping to see a clear vote to Remain.

Five years of social and political reform with Fine Gael and Labour

Five years ago we entered an election in circumstances which were embarrassing for our country. The outgoing government had just entered a bailout agreement with the Troika of the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund. Unemployment was at 14.3%.

The global economic situation has improved, and Ireland has more than taken advantage of it. We are now the fastest growing economy in the EU, with unemployment at 8.8% and falling, and a steadily improving rate of job creation. We have regained a position of respect within the European Union. This was done under the guidance of the Troika institutions, a program Ireland successfully exited from. Ireland compares very favourably to other countries which were very badly affected by the global economic crisis. This government of Fine Gael and Labour deserves credit for this stewardship of the economy.

No government shifts and improves a country’s budgetary position and economic standing as significantly as has been done here without taking decisions which merit or deserve criticism. This can be particularly said in the area of housing. However, what matters most is that there is a strong environment favouring job creation and growing incomes, to create the resources to tackle these problems, whether privately or by government.

But apart from the improved economic situation, there are many other ways in which we are a changed country since early 2011. We have seen a significant program of positive law reform.

It is now a crime to withhold information on the abuse of children. Our Taoiseach Enda Kenny spoke out strongly in the Dáil, condemning the role of the Roman Catholic Church and the Vatican in covering up the sexual abuse of children, the first Taoiseach to do so in clear and unambiguous terms. Children are now specifically protected in the Constitution, so that their voice can be heard in the legal process and their best interests considered.

Instead of filing in the District Court, in between regular business there, new Irish citizens now swear their allegiance in welcoming and open Citizenship Ceremonies.

After a wait of 21 years, and many governments, we finally had legislation in response to the X Case, which activists had called for since the judgment, legislation which certainly came at political cost, the first change to abortion law in this country since 1861. I would support more extensive reform, but this is as far as our current constitutional position allows, and it made space for debate on the next stage from here.

Local authorities now have the power to alter the local property tax within a range of 15% on either side of a base rate, giving much greater meaning and effect to local elections than before. The next Ceann Comhairle will be elected by secret ballot of TDs, creating a measure of independence from the government.

Reform of minor sentencing now allows for fines by installments, rather than needlessly sending people for short prison sentences.

We had the beginning of the process of school divestment from religious management, though admittedly this has been a process that has been slower than desired.

Gender quotas for candidate selection at general elections were introduced; though it will take more than one election to have an effect on the makeup of the Dáil, it is the beginning of a process.

A new Register of Lobbyists was created to monitor corruption in public services and provision.

The government called a vote on marriage equality, and with so many others too, strongly campaigned for a Yes vote. Both parties did so enthusiastically, and our country had a moment of pride on the world stage when we became the first in the world to vote in support of equal marriage in a popular referendum, in a campaign that captured the public imagination.

Last year also saw the enactment of one of the best gender recognition laws worldwide, with provision within the act itself for progressive review in two years’ time.

The Children and Family Relationships Act was the most comprehensive review of family law since the 1960s, which among its many provisions, gave fathers greater automatic guardianship in cases of cohabitation, allowed cohabiting couples or civil partners as well as married couples to adopt jointly, and provided for donor-assisted reproduction.

Changes to equality law mean that the ethos of a school or hospital can no longer be the basis of employment discrimination solely on the basis of personal characteristics like sexuality, or family status, or any of the other grounds of anti-discrimination.

I will be voting for a return of this government of Fine Gael and Labour. I do not expect it to be returned to office. But I do expect that it will be remembered as a reforming government, and that these many reforms will stand well to this country, improving the lives of those who live here in many small and significant ways, allowing us to continue to become a more open society.

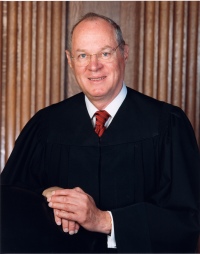

The Supreme Court without Scalia

Abortion. Affirmative action. Contraception mandates. Immigration. One person one vote. Public sector labour unions. Each of these remain as matters for the now eight justices of the United States Supreme Court to decide this term.

Many of these would have been the blockbuster end-of-term 5-4 decisions. Many of these were the result of strategic litigation or legislation by conservatives designed to test current Supreme Court doctrine. The four liberal justices of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan will very likely remain a clear bloc in these. Of the remaining conservative justices, Chief Justice John Roberts and particularly Anthony Kennedy would be expected to join the liberal justices on some of these matters, with Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito unlikely to be with them on any of these. If the court splits 4-4, the decision of the Circuit Court of Appeals stands, with no precedential weight outside of the circuit area. As outlined by Linda Hirshman in December, because of the composition of the circuit courts of appeals, this will tend to favour the liberals. But let us consider each of these major cases in detail.

Many of these would have been the blockbuster end-of-term 5-4 decisions. Many of these were the result of strategic litigation or legislation by conservatives designed to test current Supreme Court doctrine. The four liberal justices of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan will very likely remain a clear bloc in these. Of the remaining conservative justices, Chief Justice John Roberts and particularly Anthony Kennedy would be expected to join the liberal justices on some of these matters, with Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito unlikely to be with them on any of these. If the court splits 4-4, the decision of the Circuit Court of Appeals stands, with no precedential weight outside of the circuit area. As outlined by Linda Hirshman in December, because of the composition of the circuit courts of appeals, this will tend to favour the liberals. But let us consider each of these major cases in detail.

Therefore, the unexpected death of Antonin Scalia will have quite an effect on each of these, if we take Senate Republicans at their word, that they will not support any successor proposed by Barack Obama.

Abortion: Whole Woman’s Health v Hellerstedt

Abortion restrictions in the United States are currently subject to the “undue burden” test of Planned Parenthood v Casey (1992), a plurality opinion jointly written by Anthony Kennedy, Sandra Day O’Connor and David Souter. The court upheld provisions of a Pennsylvania law requiring a 24-hour waiting period, parental consent, a restrictive definition of medical emergency, and reporting requirements for abortion services. They held that requiring spousal notice of an abortion was such an undue burden.

Ferriter has before exhibited many of the faults he found with Coogan’s work

Diarmuid Ferriter may be right about everything he has to criticise Tim Pat Coogan for, but should Ferriter be the one to say it? Too many of his comments brought to mind Ferriter’s own 2004 book, “The Transformation of Ireland, 1900–2000”. This was a book badly in need of an editor, or at least another set of eyes before it launched itself on the Christmas market. At several points he makes reference to people by their profession or position but without identifying them, as if he had written an incomplete note in his research, “a leading Irish MEP suggested racism was endemic” (who? I’d love to know!), “In January 1980, Latin America’s leading Catholic theologian suggested” (what was their name?). Other times he quotes someone without giving an endnote citation, such as a line proposed by Tom Johnson, omitted from the final draft of the Democratic Programme.

At various points, he uses inaccurate descriptions for the name of the state, “Irish Republic”, “Southern Ireland”, at times when it was not appropriate to do so, or the “Free State” of a statistic in 1944. He inaccurately describes the substantive question in the 1992 abortion referendum. He mentions incidents more than once (the abolition of the industrial school system in Britain decades ahead of its abolition in Ireland; Magill’s Supreme Court victory in the prostution story); on other occasions he presents his chronology through the book in a confusing manner (writing about the resignation of Ó Dálaigh, and then the formation of the Cosgrave government; discussing Carson’s position as a Dubliner working for Ulster Unionists when discussing the formation of Northern Ireland, without any prior mention when discussing 1913; writing about talks in 1986 with the IRA two pages before talking about the hunger strikes; discussing how de Valera drafted a new Constitution without mentioning the prior deconstruction of each significant element of the Irish Free State up to 1937).

He criticised Tim Pat Coogan for inaccuracies in his dates. Yet Ferriter gives Article 44 rather than Article 41 as including a section on the life of woman in the home; he describes the Fianna Fáil as 1992-95, where in fact it was 1993-94; he gave the Progressive Democrat seat total in 1987 as 15, where in fact it was 14. He writes that university representation in the Dáil continued until 1934, where it continued up to 1937 (after an amendment in 1936). He talks of the seaside town of Bray in County Dublin, rather than County Wicklow. He describes Jack Lynch as the first Taoiseach with no Civil War baggage, without acknowledging that John A. Costello was chosen in 1948 for that reason (Lynch was the first FF Taoiseach was had not been involved in the Civil War).

There are points of lacking in clarity or precision, like referring to Holles Street, rather than calling it the National Maternity Hospital; writing in 2004, he mentions of the PDs in government from 1989-92 and 1997-2002; at one point, it seems like he’s referring to Costello as leader of Fine Gael. On what happened in Dublin at the end of the Second World, he writes, “Trinity students displayed the flags of the Allies, to which nationalist students, including future Taoiseach Charlie Haughey, responded by burning the Union Jack”; someone reading that could be forgiven for thinking Haughey went to Trinity. His discussion of the First Dáil would have been the perfect time to explain what a TD was; instead, we find it in parenthesis several pages later as “James Collins, a member of the Abbeyfeale IRA and future TD (member of parliament)”. Or even include it in a key to terms. It just looks out of place randomly there.

Some obvious points of context are lacking: for example, mentioning Mary Robinson as a presidential candidate simply as “a liberal academic lawyer from Trinity College”, without specifying any of the causes she was involved in, or that she had a career in the Seanad, or that she had left Labour in 1985, or anything else. He writes that after 1977, the electorate rejected single-party government for the rest of the century; though there were no further single-party majorities, it ignores Haughey in 1982 and 1987-89. He mentions that the 1982-87 government spent time on cultural questions like abortion and divorce, but without mentioning that there were any referendums, let alone what the result of them was. He mentions the Anglo-Irish Agreement parenthetically, while discussing the relationship between Dublin and nationalists, without explaining what it was, who signed it, who opposed it, what led to it. He talks of the response to the hunger strikes and the success of Sinn Féin in the 1980s without mentioning their change of leadership and policy on abstention.

Aside from this, there are structural problems with the book. He divides the century at decade points too rigidly at times, so that for example the discussion of the outbreak of the Troubles in the 1960s is set apart from the rest of the events that follow from it. Within each chapter, the length of any section seems to be dictated more what he can group with an amusing quotation.

There are sections of the book that read like a collection of quotations from other historians and analysts. Again and again we have lines like, “as pointed out be Laffan…”, “In the words of sports historian Paul Rouse…”, “Colm Tóibín asserted…”, “Similarly, Fintan O’Toole pointed out in his survey of Ireland…”, “Tom Garvin maintained that…”, “His alternative to the Treaty was, maintained Joe Lee…”. The occasional intext reference to other historians is fair enough, but we read a text to read the author’s interpretation of events, not see how much he likes quotations from Laffan, Lee or Jackson. He even does this doubly so once: “Michael Gallagher quoted David Thornley…”. Were it simply to survey the existing research before presenting his own thesis, it would be fair enough. But such lines are peppered throughout the text, often without any separate analysis from Ferriter.

And a few pages of an overarching conclusion would be good, to justify the title, to explain how and why he believes Ireland was indeed transformed.

Anyway, these are just a few points I noted on the margin of book at various points when I first read it, such that I thought it a bit rich for Ferriter to find the faults he did with Coogan’s book. Especially so as Coogan is a popular historian; though Ferriter writes for a broad audience, he is an academic historian, and standards of referencing and accuracy apply all the more.

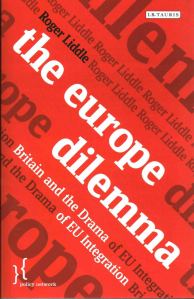

‘The Europe Dilemma’, by Roger Liddle

In September 2016, the referendum on United Kingdom membership of the European Union is likely to be held. With less than twelve months to go, The Europe Dilemma: Britain and the Drama of EU Integration by Roger Liddle, published in 2014, is valuable reading. He provides insight into how Britain’s relationship with European institutions has affected both parties. At the date of its publication, the travails of the Conservative Party was Liddle’s main focus in his conclusion; while they are still more likely to suffer internally from divisions on Europe, the debate within the Labour Party has reignited since the election of Jeremy Corbyn as leader, notwithstanding his recent commitment to remaining.

In September 2016, the referendum on United Kingdom membership of the European Union is likely to be held. With less than twelve months to go, The Europe Dilemma: Britain and the Drama of EU Integration by Roger Liddle, published in 2014, is valuable reading. He provides insight into how Britain’s relationship with European institutions has affected both parties. At the date of its publication, the travails of the Conservative Party was Liddle’s main focus in his conclusion; while they are still more likely to suffer internally from divisions on Europe, the debate within the Labour Party has reignited since the election of Jeremy Corbyn as leader, notwithstanding his recent commitment to remaining.

Lord Liddle is an unashamed europhile, whose major regret is that Tony Blair (whom he advised on European affiars) adopted an obsequiousness towards the Murdoch press that led to the United Kingdom’s non-participation in the euro single currency. In his analysis, living within the euro would have forced a tighter fiscal policy on Britain, and slowed the decline of British manufacturing.

Liddle’s case is that Britain’s leaders from Macmillan on let their country down by not participating as they could have in the European project. He argues that Britain paid a continuing price for its late arrival. Not only were they perceived with wariness by the original members, but they lost the opportunity to shape the Common Agricultural Policy, which would later become a source of grievance for the British. In Liddle’s view, the same could be said of their approach to the euro, where Britain lost an opportunity to steer it in their favour. Rather than viewing involvement in the European Union as an important venture in global politics, in positive terms, British politicians consistently talk of standing up for national interests. Liddle analyses the attitudes of the two major parties towards Europe from the 1960s to the time of his writing, both in government and in opposition, with particular spotlights on the 1975 referendum held by the Labour government on whether to remain within the EEC, and the failure of the United Kingdom to join the single currency.

David Cameron called the referendum in response to pressure from within his own party, from UKIP outside, and from the eurosceptic press. If Cameron is a moderate on Europe, Blair was an enthusiast. Yet he found himself pushed into taking stances he could not have desired. He did not stand up to those who were less committed, many of whom were part of the New Labour project. For example, Foreign Secretary Jack Straw insisted that there would have be a referendum on the 2004 Constitutional Treaty, which Blair initially resisted, it being less important in substance than either the Single European Act or the Maastricht Treaty. This public pledge led to the referendums in France and the Netherlands, which scuppered the Treaty (though it was substantially reformulated in the Lisbon Treaty).

Liddle also highlights Blair’s weakness against Brown, allowing him to set the terms for any entry into the single currency. It is clear that Blair had begun to have doubts about Brown as a successor, yet was unwilling to confront him in any serious way. Liddle marks out as the great conundrum of Blair’s premiership, that “if Brown was so unfit to be prime minister, why did our hero Blair allow a situation in which that became inevitable”. If instead of simply demoting Robin Cook from the Foreign Office in 2001, Blair had switched his portfolio with Brown’s, to have a more committed europhile in the exchequer, he might have achieved the legacy he intended of bringing Britain into the euro.

However, Blair receives praise for his commitment to enlargement, and for waiving the 7-year derogation on the free movement of labour (which the Irish government under Bertie Ahern did too, to its credit). Unlike the Labour Party that fought the 2015 election, Blair continues to affirm the merits of this policy. Liddle writes that is “depressing that the entire British political class has run away from explaining the benefits of eastern migration to economy and society”.

Liddle is naturally more critical still of Cameron, in decisions such as Britain’s opt-out of the Stability Treaty, of which he writes that it “did wonders for his rating in the party and the country, but at the price of severe damage to national interests”. His Bloomberg speech, in which he announced his intentions to renegotiate Britain’s membership of the EU, paradoxically couched Britain’s in more positive terms than anything from a Tory leader since Major in Bonn in 1990. Cameron now finds himself looking for a symbolic gesture to present to the British public in a referendum, just as Harold Wilson found presenting a change in New Zealand milk quotas as a significant renegotiation. I would also speculate that Cameron is privately more open to immigration than his push to drive down numbers entering Britain would suggest.

Cameron should not believe that by putting this referendum, which he hopes and expects to win, that he will settle the European question for a generation, or give him rest from the anti-EU sections of his party. Such are the lessons of history from the Labour Party; eight years after holding a referendum in which two-thirds of voters supported remaining in the EEC, the party stood in the 1983 general election on a platform of withdrawal, and had lost many of its more pro-European members to the newly formed Social Democratic Party (later to join with the Liberal Party to become the Liberal Democrats). It took many years for the Labour Party to resolve these internal battles in the New Labour project.

The New Stateman asked this week, Can anything sink the triumphant Conservatives? With Labour out in Scotland, thanks to the SNP, and undergoing an identity crisis since Corbyn’s election (watch Shadow Justice Secretary Lord Falconer outline the differences he holds with his party leader, and these tensions are there across the shadow cabinet), it might seem like the Conservatives are indeed in for a few years of plain sailing. But if anything can put them off course, it may be this referendum, and the divisions within the party, whatever the results.

Do check out Liddle’s book over the course of this debate!

Vote Yes on Lowering the Age of Eligibility for Election to the Office of President

I will also vote Yes to lower the age of eligibility for the office of president. At 21, adult citizens are eligible to stand in a general election and from there to sit in government. I cannot see any reason why these adult citizens should be excluded from the onerous nomination and election process, for a further fourteen years. While we might not be able to imagine who such a candidate might be, who could represent the nation at such a young age, why should we be happy to make the statement that no person under 35 could have that capacity? Why exclude the possibility and limit the choice of the people absolutely in this respect?

There have been the rare examples across history of those who led movements of change at a young age, who inspired their community and their country, including from the time of the foundation of our own state. Rare as they may be, let’s not deny such a candidate the chance to put their name before the people.

Many have complained that it’s too small a reform. There are amendments I’d rather be voting on. But it made sense to hold one with the marriage referendum that wouldn’t distract from that important debate. And if even small, unobjectionable measures of political reform don’t get public support, what makes anyone think a government will be eager to make the case for a more substantial measure of political constitutional reform?

Why a Yes vote on Marriage Equality this Friday matters to me

This is the sixth referendum campaign I’ve taken part in. I’ve also been to the count centre after every general and local election since 1997. I was emotionally invested in the result on each occasion. I have both great and difficult memories from those count days. Yet I will watch the results come in on Saturday with more trepidation than ever before. This isn’t normal politics, whether in the distribution of resources, or arrangements of political structures. This referendum is about me, and others like me, a political decision on our lives and relationships, and our place in Irish society.

It is the natural step in the decline of animosity and the growth of empathy towards lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in Ireland and elsewhere, that we would have the same opportunity to marry as anyone else. Slowly at first, and then in rapid succession, other countries and territories have come to view the limitation of marriage to heterosexual couples as an unjust exclusion, and changed their laws to reflect this new insight and understanding.

We have seen since the beginning of this year in particular what a Yes vote would mean to so many people, what a difference it would make. Those who were quiet for decades about this part of their lives, silent even to themselves, who felt compelled to speak out. And felt so much better for it. And we can think of young people, beginning to realize their difference from their peers, how wonderful the effect of a Yes vote would be for them, how devastating the effect of a No vote.

Being gay is not a small part of who I am. It doesn’t feel right to say that I just happen to be gay. It is not an incidental feature like height or hair colour, but a distinguishing feature of one of the relationships most important to me. From when I properly realized that future romantic relationships would most likely be with other men, it was something I could not but see as an important part of who I am. Indeed, it was before then, though I did not yet fully realize it. It is important because of where we now stand in society. A successful result will allow us each to determine its significance for ourselves. I look forward to the idea that my romantic life will no longer be a political issue.

This isn’t about any need for validation, but a commitment that society should treat us all with equal concern and respect, and that where the state is involved in our lives, our laws should recognize our equal dignity. With civil partnership and family law reform in place, to withhold marriage is such an arbitrary and needless act of discrimination.

When I attended a wedding service of two friends of mine earlier this year, something that stood out is our part in that. Not only did they commit to each other, for better, for worse, but we, the community of friends and family gathered there, also pledged to stand by them. The vote this Friday is that moment writ large. It is a chance to say clearly that when two people choose to make this commitment, we will stand by them, and hold their relationship as something to value.

So vote Yes. Be part of what should be a great moment for so many of us. Plan your trip to the polling station on Friday, and make sure others you know have done the same. Every vote will send a message, and every Yes vote will help secure a more equal Ireland.

Will John Roberts find a constitutional right to equal marriage?

John Roberts, Chief Justice of the United States (from Wikipedia)

Chief Justice John Roberts is usually a reliable vote among the conservatives on the nine-member court. Yet in NFIB v Sibelius (2012), he voted with the four liberals to find that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was constitutional. He did so on narrower grounds than the four liberals, relying on the taxation power rather than the commerce clause. It is widely accepted that Roberts had originally intended to strike down the law, but changed his mind in the month beforehand, based in part on the political calculus that it would damage the Court’s political reputation were it to strike down Barack Obama’s key legislative achievement. It would have appeared too partisan for the five justices appointed by Republican presidents to vote to strike it down, with the four appointed by Democratic presidents to vote to uphold it, and affected the court’s reputation as a neutral umpire calling ball and strikes.

The ACA is back before the court this term, in King v Burwell, not on the validity of the law, but its application. But if Roberts did not hinder it in 2012, he is unlikely to do so now after so many have already taken advantage of it. And in this case, he has cover from Anthony Kennedy, who voted against the ACA in NFIB, seems likely to uphold its application in this case.

The blockbuster case of this term is Obergefell v Hodges and its related cases, which will be heard this Tuesday, and is likely to settle the question of equal marriage for gay couples in the United States. The court themselves admit the difference between it and other cases this term with a link to briefs for the case on their home page, and agreeing to release the audio recording of oral argument on Tuesday, rather than waiting till the end of the week as standard.

There’s no reason to expect that any of the five justices who struck down the Defense of Marriage Act in United States v Windsor (2013) will not apply similar reasoning to state bans on same-sex marriage. But Roberts was in the minority in Windsor. Why would he vote to strike down these bans at a state level if he would not do that to the federal legislation two years ago?

John Roberts was appointed as Chief Justice in 2005 at the age of 50. Four of the associate justices are aged between 76 and 82. We should expect that Roberts will remain leading the court till at least 2030. Roberts is politically astute enough to know that this case will be regarded as a landmark. Will he want to risk the opprobrium of legal analysts in a decade’s time appearing before him wondering how he could have got it so wrong? It’s easier for Antonin Scalia, not being in the pole position of Chief Justice, or indeed Samuel Alito, who like Roberts was appointed in 2005 by George W. Bush.

Scalia and Alito both gave lengthy dissents in Windsor, with which Clarence Thomas joined. Roberts, by contrast, wrote a succinct dissent, of a mere three pages. He joined Scalia only on the jurisdictional matter, finding that the court should not have decided the case at all, as the United States government was not contesting Edie Windsor’s claim. Roberts’ short dissent justified the Defense of Marriage Act on the basis of uniformity of marriage rules, rather than the blistering terms of Scalia’s dissent defending the enforcement of traditional moral and sexual norms.

Might Roberts wish to deprive Kennedy the pleasure of his place in history of completing a series of judgments in favour of constitutional protection to gay people. From Romer v Evans (1996), to Lawrence v Texas (2003), to United States v Windsor (2013), Anthony Kennedy wrote all of the case law progressing gay equality. Eric Segall recently wrote about the rivalry between Roberts and Kennedy for perceived control of the court.

The author who writes opinion of the court is assigned by the most senior justice in the majority. If the majority is the same five as in Windsor, that would be Anthony Kennedy, who will surely assign it to himself. But if Roberts were to join the majority as the sixth vote in favour of requiring all states to license a marriage between two people of the same sex, he could then choose to assign the opinion to himself.

So, both because he should be able to project the landmark status of the decision, and because of rivalry with the other moderate conservative voice, don’t be surprised if Roberts strikes down the bans. But aside from the politics of it, there’s nothing in any of his other votes on social reform cases to suggest that he will do so!

Of course Justice Kennedy will vote for equal marriage

So the United States Supreme Court has granted certiorari in from cases on state bans on the marriage of gay and lesbian couples: Obergefell v Hodges (from Ohio), Tanco v Haslam (Tennessee), DeBoer v Snyder (Michigan), and Bourke v Beshear (Kentucky). These are appeals of the opinion of Judge Sutton in the Sixth Circuit, who found state bans to be constitutional in November, while the Fourth, Seventh and Tenth Circuit Courts had previously ruled against state bans.

There will be two questions before the Supreme Court:

- Does the Fourteenth Amendment require a state to license a marriage between two people of the same sex?

- Does the Fourteenth Amendment require a state to recognize a marriage between two people of the same sex when their marriage was lawfully licensed and performed out-of-state?

I fully expect them to answer both questions in the affirmative, reversing the judgment of Judge Sutton, recognising a constitutional guarantee of equal civil marriage in all fifty states.

Speculation has already focused on Anthony Kennedy. They are right to do so but not as a swing vote who could go yea or nay on either side. Most analysis factors in the likely breakdown of the court as four liberal justices likely to strike down states bans (Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor and Kagan) and four conservative justices likely to uphold them (Roberts CJ, Scalia, Thomas and Alito), with Anthony Kennedy as the swing vote. To my mind, this mischaracterises the record of Kennedy on this topic, and the role he is likely to play when it comes to the opinion of the court (simplistic as any categorization of justices is, even as I divide them here).

The US Supreme Court has issued three full opinions which extended constitutional protections to gay people against discrimination by government: Romer v Evans (1996), striking down an amendment to the Colorado constitution denying protected status to homosexual or bisexual people; Lawrence v Texas (2003), striking down anti-sodomy laws in Texas, and consequently in 13 other states; and US v Windsor (2013), striking down Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act, which recognized only marriage between a man and a woman for federal purposes. The author of all three opinions was Anthony Kennedy. None of these were equivocal or half-hearted. What makes anyone think he’ll go thus far and no further? Read more…

Stand by the open society

Yesterday we saw a murderous attack in Paris because Charlie Hebdo, a satirical magazine, engaged in their right of self-expression. This is a fundamental human right, derived from the right each of us has to our own thoughts and mind, which is toothless without the ability to express this. This principle is meaningless if it defends and safeguards only various shades of grey. Oliver Wendell Holmes saw the value “freedom for the thought we hate” in 1929 (then in the minority, now an accepted part of US Supreme Court jurisprudence). The European Court of Human Rights described this in 1976 as “one of the basic conditions for the progress of a democratic society and for the development of every man”. They went on to find that it “is applicable not only to information or ideas that are favourably received or regarded as inoffensive or as a matter of indifference, but also to those that offend, shock or disturb the State or any sector of the population”.

Satire has a long and venerable tradition in Europe, with its heyday in the political cartoons of the eighteenth century. Satire is not something designed or set out to be responsible or respectful.

But a liberal society is not devoid of the notion of personal responsibility. We are each responsible for our own actions and reactions. Outside of the specific and restricted partial legal defence of provocation from a temporary loss of control, we may not claim the behaviour of another to justify our own actions. Those who murdered journalists and the protection did so in full control of their senses, and must be held accountable for these actions.

It also means we hold them responsible, and not their own community and culture. We captured, they should be tried as any murderer would be, to the full rigours and with full due course of law.

And in standing by an open society, we should do more than defend full freedom of speech. We should also affirm the value of a liberal, tolerant society. Yes, we will permit satirists to mock religious beliefs. We will also allow religious communities to organise without discrimination. We should not question without good cause the differences of different customs. We must respect the individual rights of all; this means those who wish to wear a veil should be allowed to do so, whether or not we agree with the custom. One religion or another, or having none like myself, should neither confer advantage nor cause an obstacle.

This is not a time to divide one against the other, separate those living in countries based on the length of time of their various ancestry.

Without seeing any duty on those within particular communities to condemn or not to condemn actions of others no reasonable could endorse, we can also take time to recognise and value those within the Muslim community who are speaking against the barbarism committed in the name of their faith:

If we believe in the liberal values which were highlighted in our culture in the Enlightenment, but which have existed to varying degrees in nearly all cultures, and I certainly do, the attacks yesterday should not be seen as a test of them, but a reason to reaffirm them. We should aim towards an open society, where all are free to speak their mind, whether different cultures can mix, and learn from each other. A society where it is expected that we will not share in our sensibilities, that eschews uniformity and cultural stagnation. A society that strives to treat all truly equally before the law, not just in the court system, but in the administration of the state. This can be a society where each individual can thrive in the way they define for themselves, to make our choices in life. And this resilient observance of individual freedom could well be the only way our society will survive.

And Colorado makes it 25. How long before the Supreme Court brings it to 50?

Today, the US Supreme Court denied certiorari to challenges to decisions of the Fourth, Seventh and Tenth Circuit Courts of Appeal, which had in turn upheld decisions of federal district courts that bans on lesbian and gay couples from marrying in Indiana, Oklahoma, Utah, Virginia, and Wisconsin contravened provisions of the US Constitution.

This had the immediate consequence of bringing equal civil marriage to these five states. The effect of supreme court not taking a decision led to the biggest expansion by number of states seen to date.

The day continued, as Colorado dropped its challenge. So how does the Circuit system work, and which states could be next?

Beneath the Supreme Court, the United States is administered by geographically-based courts of appeals. This table details the division, with those states which at the time of writing have equal civil marriage for gay and lesbian couples highlighted in bold:

| 1st | Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island |

| 2nd | Connecticut, New York, Vermont |

| 3rd | Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania |

| 4th | Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia |

| 5th | Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas |

| 6th | Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio, Tennessee |

| 7th | Illinois, Indiana, Wisconsin |

| 8th | Arkansas, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota |

| 9th | Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Washington |

| 10th | Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Utah, Wyoming |

| 11th | Alabama, Florida, Georgia |

| DC | District of Columbia |

A rule of precedent applies at each of these levels. The district courts in the states are bound by decisions of the court of appeals of their own circuit, just as the circuit courts of appeal are bound by the supreme court. This is why the attorney-general in Colorado dropped the challenge so soon after the news today; with the decisions of the tenth circuit court of appeals that found bans in Utah and Oklahoma to be unconstitutional fully in effect, the same would result with any defence of the ban in Colorado.

We should then soon see a similar situation in North Carolina, South Carolina and West Virginia in the Fourth Circuit, and in Kansas and Wyoming in the Tenth, from a combination of state officials not defending the bans, and district court judges coming to swift decisions based on these precedents.

We are awaiting decisions from the Sixth Circuit, which heard arguments in the beginning of August, and from the Ninth Circuit, which heard arguments at the beginning of September. While the court in the Ninth Circuit seemed to follow the trend of most federal courts, in being more critical of the arguments for maintaining the bans, this is less certain in the Sixth Circuit. Listening to the oral argument, I would agree with Stern that Judge Sutton didn’t seem eager to press ahead with this. However, a few things have changed since early August, from Judge Posner’s excellent, cutting judgment in the Seventh Circuit, to the denial of cert by the Supreme Court today.

In the Sixth Circuit, Judge Sutton asked on a number of occasions why he would not be bound by the precedent of the Supreme Court in Baker v Nelson (1971), in which the court wrote succinctly on a Minnesota case on a gay couple, “The appeal is dismissed for want of a substantial federal question”. This was a mandatory review, so was considered binding on the merits. However, with the denial of cert today, Judge Sutton can no longer hide behind Baker, as the Supreme Court has effectively that it doesn’t see the decisions favouring equality as a challenge to its precedent.

I don’t think the Supreme Court will hear a case unless and until any of the circuit courts uphold the constitutionality of a state ban. This could occur in the Sixth Circuit; it could also occur in the Fifth Circuit, which will be hearing cases relating to Texas and Louisiana soon. These are appeals to ban in Texas which was struck down, and a ban in Louisiana which will be upheld.

Equality advocates want the Supreme Court to hear a case on this matter sooner rather than later, to lead to an opinion that with one fell swoop would bring equal civil marriage to gay and lesbian couples across the whole of the United States. There is little reason to suppose that any of the five who voted to strike down a section of the Defense of Marriage Act in United States v Windsor (2013) would not also strike down all bans as unconstitutional, least of all the one who wrote that judgment, Justice Anthony Kennedy. The four who would have upheld DOMA surely suppose the same thing of their colleagues as the rest of us.

There is another interest too here, that of standing by the sovereignty and competence of lower courts. It is within their remit to determine constitutional questions within their jurisdiction; the Supreme Court should not hear a case simply because there’s public demand for a decision of a lower court to be extended.

It takes four justices to grant cert to a case. In the case of these circuit decisions, the five were of course happy to let them stand; the four may not have agreed with them, but not either wish to hasten the moment when the court would rule for equality for all.

This is why supporters of equality might paradoxically hope that either the Fifth or Sixth Circuit Courts of Appeals will decide to uphold bans. Not only would there then be a circuit split, but a result the anti-DOMA 5 would surely feel confident to see challenged before the whole court.

We’ll wait and see.

Why marriage might return to the US Supreme Court and why this time it’s different

The new term of the US Supreme Court begins today, and their docket for this term will begin to fill up. The nine members of the court decide themselves which cases to hear, of the many appeals from lower court decisions across the country. Among they many they could choose this term are a number of defences to state bans on either the recognition or performance of marriage between couples of the same sex. This would lead to a decision affecting all US states by June 2015. It is not long since the Supreme Court last considered cases relating to marriage, when they ruled on United States v Windsor in 2013, leading the federal recognition of marriages between same-sex couples as performed by these states. Why makes these cases different?

A lot of the commentary in June 2013 spoke of the compromise the court reached, in striking down the ban on federal recognition in Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), while declining to consider the implications of the other case before it beyond California. This is a simplistic view of that case. This second case that year was Hollingsworth v Perry, a case which originated as Perry v Schwarzenegger, the culmination of a challenge to Proposition 8, the 2008 ballot initiative which had added to the California constitution the clause, “Only marriage between a man and a woman is valid or recognized in California”. In August 2010, US District Court Judge Vaughn Walker became the first of many federal judges to find a ban on same-sex marriage to contravene the US constitution. The state of California accepted the court’s ruling, and the appeal was taken up by those who had campaigned for Proposition 8. The Supreme Court that they did not have standing to do so, i.e. they did not have a direct stake in the outcome. It remained a matter for an organ of the state to defend a state law. Rather than being a formula drafted to dodge addressing a hot-button issue too soon, it would have been more questionable had they decided to consider the case. In 1996, the court came to a similar conclusion in Arizonans for Official English v Arizona, and the court should adhere to its precedents unless there are clear and compelling reasons to revisit a previous ruling.

A lot of the commentary in June 2013 spoke of the compromise the court reached, in striking down the ban on federal recognition in Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), while declining to consider the implications of the other case before it beyond California. This is a simplistic view of that case. This second case that year was Hollingsworth v Perry, a case which originated as Perry v Schwarzenegger, the culmination of a challenge to Proposition 8, the 2008 ballot initiative which had added to the California constitution the clause, “Only marriage between a man and a woman is valid or recognized in California”. In August 2010, US District Court Judge Vaughn Walker became the first of many federal judges to find a ban on same-sex marriage to contravene the US constitution. The state of California accepted the court’s ruling, and the appeal was taken up by those who had campaigned for Proposition 8. The Supreme Court that they did not have standing to do so, i.e. they did not have a direct stake in the outcome. It remained a matter for an organ of the state to defend a state law. Rather than being a formula drafted to dodge addressing a hot-button issue too soon, it would have been more questionable had they decided to consider the case. In 1996, the court came to a similar conclusion in Arizonans for Official English v Arizona, and the court should adhere to its precedents unless there are clear and compelling reasons to revisit a previous ruling.

Windsor ruled on Section 3 of DOMA, as this was the only question before it in that case. Writing the opinion of the court, Justice Anthony Kennedy held in clear and eloquent terms that the provision was unconstitutional. He wrote with an understanding of the change in attitudes we are witnessing, “until recent years, many citizens had not even considered the possibility that two persons of the same sex might aspire to occupy the same status and dignity as that of a man and woman in lawful marriage … Slowly at first and then in rapid course, the laws of New York came to acknowledge the urgency of this issue for same-sex couples who wanted to affirm their commitment to one another before their children, their family, their friends, and their community”. After acknowledging the many harms of such a ban on recognition, including to the children of same-sex couples, Kennedy concluded “What has been explained to this point should more than suffice to establish that the principal purpose and the necessary effect of this law are to demean those persons who are in a lawful same-sex marriage. This requires the Court to hold, as it now does, that DOMA is unconstitutional as a deprivation of the liberty of the person protected by the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution. The liberty protected by the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause contains within it the prohibition against denying to any person the equal protection of the laws.”

While Justice Kennedy did spend a considerable portion of the opinion defending the right of the states against the federal government in relation to marriage, this was in support of New York in including same-sex couples. Citing Loving v. Virginia (the 1967 case which ended state bans on interracial marriage), he wrote “State laws defining and regulating marriage, of course, must respect the constitutional rights of persons”.

Following this judgment, many cases proceeded in federal district courts challenging state bans. The first judgment was in December 2013 in Utah, where Judge Robert Shelby cited not only the opinion of Kennedy in Windsor, but also the dissenting opinion of Justice Antonin Scalia, who predicted that it would be a very small step from striking down the federal provisions in DOMA to striking down the bans in the states. Ten other district court judges came to the same conclusion when considering state bans across the country, ruling each of them unconstitutional; in September, Judge Martin Feldman in Louisiana became the first to write a court opinion upholding such a ban.

While some of these decisions applied with brief effect, most of them were stayed pending further appeal, so marriage has not been extended in these states (Pennsylvania being an exception, where the state accepted the opinion of the district court).

The Circuit Court Appeals have issued opinions in the Tenth Circuit (cases from Utah and Oklahoma), in the Fourth Circuit (from Virginia), and in the Seventh Circuit (cases from Wisconsin and Indiana), and in all cases upholding decisions that state bans are unconstitutional. Crucially, in all these cases, officials from the state are defending the ban, distinguishing them from the situation in California.

The Supreme Court may now decide to take any one or all of these cases. If they choose not to hear those cases this term, then the circuit court decisions will stand, and marriage will be extended in those states, and nearly immediately in other states in those districts. However, the supreme court may wish to wait until there is a circuit split, i.e. when there are conflicting interpretations of the constitution from different circuit courts. It remains possible that appeals in other circuits will find in favour of the constitutionality of state bans; this seems quite likely to be the outcome in the Sixth Circuit, where Judge Jeffrey Sutton was quite skeptical of the merits of the constitutional case for equal marriage at oral argument in cases from Michigan, Kentucky, Tennessee and Ohio. If this occurs, it is almost certain that they will be heard this year.

While those of us following the developments will wait eagerly to hear from the court today, I wouldn’t be holding my breath. In 2013, I tuned in on a weekly basis to whether they would take the Perry case, and which DOMA case they would consider; it was not until 7 December that this information was revealed.

Which still means that before Christmas, we should expect to know of a date in the spring when the Supreme Court will hear cases relating to the constitutionality of bans across the whole United States, with an opinion in June. I will of course return to this, to outline in clear terms why I believe they both should and will find that there is a constitutional right for couples of the same sex to marry, throughout the United States.

Scottish Independence vote

I arrived in Edinburgh this afternoon, less than a day before polls open in the most important vote they’re to have here in surely any of their lives. I had long planned to visit the land of Adam Smith and David Hume, but to be here for this vote is definitely an added bonus.

While the media cling to that trope of any poll in the high 40s of it being too close to call, I’d be quite surprised if this were to pass. I’m not sure either how much I’d be pleased or excited either way; but what would place me as a slight Yes supporter is a gut instinct that they can do it alone, that they can confound the fears supposed by No campaigners and Unionist leaders south of the border. I think an independent Scotland could thrive, just as we in Ireland did, or other small European countries like Denmark or Norway have too. In the longer run, I don’t see the structural benefits of being part of the United Kingdom, or the difficulty in leaving it, would outweigh the benefits to managing their own affairs.

A few things have struck me about the campaign. To be domestic about it, I’m surprised how little Ireland has featured as an example in this debate. Being a neighbouring isle with a border with different currencies, and the only other instance of a departure from the United Kingdom. Granted, there often seems to be a mist of ignorance for many in Britain surrounding the constitutional status of either part of Ireland. But we’d surely be a relevant context.

This referendum seems like it could only have got this close for independence with a Conservative Prime Minister in Downing Street. It’s notable how much this has been about social policy. Perhaps they assume it’s taken for granted by voters, but I’d have expected more emphasis on how Scotland would be taking its place among the nations of the world, a seat at the United Nations, a European Commissioner, embassies worldwide. That angle might have been a response to those who wondered how it differed from devo-max.

The left-leaning nature of the politics at the moment makes me curious about how politics might have evolved under independence, might the Scottish Nationalist Party have adopted a more centrist stand, to be perhaps the equivalent of Fianna Fáil. And would the other parties have changed their names, to break the link with their southern counterparts to broaden their base. Would the Scottish Conservatives again become the Progressive Party?

The currency and Scotland’s place within the European Union under independence remain uncertain. To some extent, they’re linked, as new members are committed to join the euro when they can. Scotland may well try to continue to use sterling without a tie to the Bank of England, and use the United Kingdom’s Maastricht opt-out. That will be difficult. But in the unlikely event of a Yes vote on Friday morning, I believe Ireland should act as a friendly neighbour, with whom we have some cultural ties, and do what we can to facilitate their entry/continuation in the EU, and compete with them ruthlessly too when we can!

Winning the Marriage Referendum: A Simple Message

As part of Dublin Pride, GLEN hosted a meeting in Wood Quay entitled, How to Win a Referendum. It was great to see such a large turnout, full to capacity, and a meeting focused on getting us over the line.

It will be a tough eleven to sixteen months (based on different estimates of when the poll will actually be). With a good campaign, I’m confident we can win this. But we need this good campaign, and to be prepared for all that could emerge. Tiernan Brady, who hosted the proceedings, closed by saying that if each of us can sleep easy when polls close knowing that there was nothing more we could have done, no one else we could have talked to, then we can look forward to the result the next day. That is no small task.

We need a simple, clear message. There is so much that could be said about the marriage question and the history and development of the acceptance of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people in Ireland and across the world, moving to a place where we can be integrated as we wish in society, while also celebrating our distinctive identities and culture. We could go on at length, having what would doubtless be worthwhile discussions. Some of this will emerge over the course of the campaign, and I wouldn’t seek to repress it.

But most of the voting public will hear but a fraction of the debate. We need to ensure that there is a dominant message in the campaign, one which they can relate to and understand. Why it matters that they vote Yes to this proposition.

I see three prongs that should be emphasised, to different degrees. The extent or the order we might emphasise these would depend on the platform, who you are engaging with, what they are raising, and how long you have with them. Marcella Corcoran Kennedy spoke of a conversation with a fellow passenger a train journey; that might give someone half an hour. On an evening canvass, you might be lucky to get ten seconds with someone at their door.

First, we should establish why marriage matters. Media debates on this question get caught up sometimes with a definition of marriage. But marriage has changed over the course of human existence, it is as varied across time and place as societies themselves have changed or continue to be different. Nevertheless, there are certain elements that remain true, certainly within generations in Ireland. Marriage both creates and extends a family. It is a public statement of the commitment of two people for each other, for richer, for poorer, in sickness, in health. It means being there for someone, looking out for them. If we get the chance to engage with people who are themselves married, ask them what it means to them.

Then we have the substantive issue, why it matters for us. The significance of being able to celebrate your lives together and love for each other in a way that has such universal understanding. Or if not you personally, your gay friend, your lesbian sister, your bi neighbour. That there should not be a distinction between the love and commitment of one couple and that of another. We need to hear whole families talk, parents talking about the love each of their children have found, and that what matters is not whether the person who their son or daughter wishes to marry is a man or a woman, but that it is someone who will be there for them. Not only will the uncertain voter connect more with a personal story than about a more generic message about a tolerant society, they will also be brought much closer to understanding the question and its meaning. The focus should not just be on the couples either, but also on the children currently raised by gay couples. Focus on the opportunity it gives them, that their parents could be treated just others, not to grow up with society making this distinction.

Third is the reassurance. That the second does not in any way detract from the principle of the first, but enhances it. That this is an opportunity to reaffirm the value of marriage in society. And also to engage with the question of religious marriage. We cannot ignore the fact that the vast majority of people in the country are either religiously observant or retain instinctive attachment to their faith. This should not be approached from a perspective of church against state. Each denomination and faith will of course continue to be free to make their own decisions about marriage as a religious sacrament. All the referendum seeks to do is to allow gay couples wed in the civil institution of marriage. Allowing this will improve the lives of these couples and their families, without in any way affecting marriage for anyone else.

But all this is has been far too long. We need to continue to find ways to distil the essence of these elements of the case in shorter, more concise forms. And that is but one part of the work ahead.